Vickie Mullins recalls a traumatic moment in her 8-year-old grandson’s life.

She said the family, who live in Cumberland County’s Cedar Creek Township, near the Bladen County line, were visiting relatives in the mountains last summer when her grandson saw something that caused a visceral reaction. Mullins said that when his older brother grabbed a glass and went to the sink to fill it with water, the younger brother lost it.

“All of a sudden, he starts yelling, ‘Don’t turn on that water!’” Mullins said. “He was screaming, ‘You know we’re not allowed to drink water from a spigot!’”

Mullins said she was crying as she bent down, hugged him and told him: “This is how normal people live.”

Living under the shadow of contamination from per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances — also known as PFAS or “forever chemicals” — has robbed Mullins’ grandchildren of some of life’s simple pleasures.

“He’s always cried, wanting to take a bath, but we don’t let him […] How do you tell an 8-year-old that he can’t play in a bubble bath?”

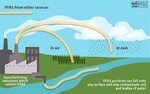

There are thousands of the manmade chemicals known as PFAS in the environment, according to experts, and more are being discovered. The compounds are ubiquitous — found in such items as cosmetics, nonstick cookware, upholstery, water-resistant fabrics used in raincoats, umbrellas and tents, microwave popcorn wrappers and dental floss.

PFAS compounds accumulate in people’s bodies, and researchers have found evidence that suggests a link between PFAS exposure and weaker antibody responses against infections, elevated cholesterol levels, decreased fetal and infant growth, and kidney cancer in adults, among other problems.

What’s more, a study published in December 2023 found that children with prenatal exposure to two types of PFAS compounds — perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) and perfluorononanoate (PFNA) — were more likely to experience childhood obesity.

Mullin’s grandson was 3 in 2019 when Chemours, the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality and Cape Fear River Watch established a consent order with the state and an environmental group consent order. The order requires Chemours to “address PFAS sources and contamination at the facility to prevent further impacts to air, soil, groundwater, and surface waters,’ according to N.C. DEQ.

But Dana Sargent, executive director of Cape Fear River Watch — the Wilmington-based environmental organization which was party to the consent order — argues that the mandate doesn’t go far enough.

Under the consent order, Chemours “is only testing for 12 PFAS,” she told an audience gathered at Gaston Brewing in Fayetteville on Jan. 31 to view a screening of the WRAL documentary Forever Chemicals: North Carolina’s Toxic Tap Water.

She added: “The consent order also required that this company conduct what’s called a non-targeted analysis to find what we don’t know. That analysis found 257 PFAS coming out of this facility, and they’re sampling for 13? It’s ridiculous!”

There’s growing momentum across the country to address the thousands of known PFAS as an entire class, according to a report released by Safer States, a national alliance of environmental health organizations that’s working to protect people and the environment from toxic chemicals.

One of the requirements mandated by the consent order is that Chemours test private drinking wells for PFAS contamination in Bladen, Cumberland, Robeson and Sampson counties, which are near the company’s Fayetteville Works. For those whose wells have 10 parts per trillion of PFAS, Chemours is required to provide “replacement drinking water supplies.” The options range from bottled water, to a water filtration system, or a connection to the public water supply if feasible.

The Mullins family well test revealed the PFAS contamination level was 14 ppt. As a result, the family has received 30 gallons of water bi-weekly per the consent order for five years — the majority of Mullins’ 8-year-old grandson’s life — Mullins said.

In the Consent Order Progress Report, the company published that during the fourth quarter of 2023, there were 2,569 households receiving bottled water. However, many feel that the number does not reflect those whose well water contamination is just below the 10 ppt threshold, for instance, or residents who buy bottled water because they don’t trust the public water supply.

Vickie Mullins says, in addition to receiving bottled water through the consent order, she buys smaller containers of bottled water that are easier for her grandkids to handle.

Recently, the Environmental Working Group, a nonpartisan environmental advocacy organization based in Washington, D.C., reported that the Environmental Protection Agency found that 70 million U.S. residents have drinking water that tested positive for PFAS. The advocacy organization reported that the “number is based on the latest test results from only one-third of public water supplies.”

The information is contained in the EPA’s Fifth Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule report, mandated under the Safe Water Drinking Act, and was released earlier this month from tests conducted in 2023.

In 2020, the Environmental Working Group also reported that “more than 200 million Americans are served by water systems with PFOA or PFOS — two of the most notorious PFAS — in their drinking water at a concentration of 1 part per trillion, or higher.”

As if life isn’t complicated enough for people like Mullins, a study published in January by Columbia and Rutgers University researchers found that a liter-sized plastic bottle of water contains about 240,000 nanoplastic particles.

N.C. Health News has reported on the impact of microplastic pollution, including a study that suggests links between nanoplastic particles and a brain protein that may increase the risk for Parkinson’s disease and some forms of dementia. Microplastics can be as large as a pencil eraser or as small as a speck of dust.

Nanoplastic particles are even smaller than microplastics, ranging in size from 1 nanometer (about half the width of a strand of DNA) to 1 micrometer (about the width of a typical bacterium).

While there is no known link between microplastic ingestion and disease in humans, a study published in 2022 found that people with inflammatory bowel disease had more microplastic particles in their feces than healthy people. (Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are two forms of IBD.)

Toxicologist Linda Birnbaum, former director of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, said that while more research is needed, knowledge is growing when it comes to the impact of microplastics on the human body.

“We know enough now to know that the microplastics and the nanoplastics that we are using in everything are getting into us,” Birnbaum said. “And we know that the plastics often contain chemicals like PFAS, for example, or BPA, or phthalates that […] leach from the plastic and get into us. And we know that those have adverse effects.”

Beyond the risks microplastics pose to humans, not all plastics are recyclable and not all recycling programs are equal. In 2018, polyethylene terephthalate (PET), the plastic material used to make plastic water bottles, was recycled at a rate of 28.6 percent, according to a report by the Environmental Protection Agency. That same year, plastic accounted for nearly 18.5 percent of municipal landfill waste.

“The beverage sector is one of the most well-poised sectors to transition to reusable packaging — especially because many of the same companies selling Americans our drinks in disposables are selling them to the rest of the world in returnable, reusable containers,” said Sydney Harris, policy director for Upstream, a reuse advocacy group.

Birnbaum agrees that having more glass and fewer plastic containers on the market would be better for the environment and human health, but she thinks it’s a tall task.

“We need to start tremendously reducing our use of plastics, but that’s going to be very hard in a society that is almost totally dependent upon plastics,” she said.

“The fastest way to bring about change very honestly is for [consumers] to speak. If people were to start saying, ‘I don’t want to buy water in plastic bottles; I don’t want to buy my Coke or Diet Coke in plastic bottles,’” she said, “that would have an impact, but I don’t see that [happening]. It’s too easy right now.”

“While we do want to see the beverage sector transition to returnable, reusable containers,” Harris said, “that will not relieve society of the responsibility to upgrade our water supply systems and ensure communities have access to safe drinking water from the tap.”

Thinking about what she and her family have endured after discovering PFAS contamination in their well, Mullins said, “I want a normal life back for our family because this is ridiculous.”

North Carolina Health News is an independent, non-partisan, not-for-profit, statewide news organization dedicated to covering all things health care in North Carolina. Visit NCHN at northcarolinahealthnews.org. Visit the story's original link.